Profile Over Performance

In academy football, goalkeeper recruitment starts early.

From the U9 season onwards, most academies register players to be specialist goalkeepers. While this isn’t a formal regulatory requirement, it has become an operational reality. Asking an outfield player to play in goal isn’t credible, sustainable, or fair to the player, the parents, or the competition.

So academies recruit goalkeepers early because they have to in practice, even if not in theory.

The real question isn’t whether goalkeepers should be recruited early.

It’s how those early decisions are made and what they are based on.

The problem with early performance

At youngest ages, goalkeeper performance is a very poor guide to long-term potential.

At these ages, what we see on a matchday is heavily influenced by:

- Relative age

- Early physical maturity

- Confidence rather than competence

- Small-sided game chaos

- The disproportionate cost of mistakes

In simple terms, early performance often tells us who is ready now, not who will be best later.

This problem is magnified for goalkeepers, whose development curves are later, longer, and far less linear than those of outfield players.

Yet early recruitment decisions are still often shaped consciously or not by what looks effective in the moment.

“Late specialisation” is widely misunderstood

There’s a common belief that elite goalkeepers “specialise late”.

In reality, most elite English goalkeepers entered structured academy football early — typically between the ages of 8 and 10. They weren’t late starters.

What was late was certainty.

Their pathways were rarely straight lines. Some developed in smaller academies. Some were released. Some were acquired later by bigger clubs once growth, psychology, and decision-making caught up with potential.

The lesson isn’t that academies should delay recruitment.

It’s that they should delay judgement.

Why later acquisition happens

When larger academies acquire goalkeepers at 13, 14, or 15, it’s rarely because something entirely new has appeared.

It’s usually because:

- Physical growth has normalised

- Psychological traits are clearer

- Decision-making has stabilised

- Performance now aligns with underlying capacity

In effect, acquisitions often corrects for early uncertainty.

What clubs are willing to pay for later is often what was already there earlier just harder to evidence.

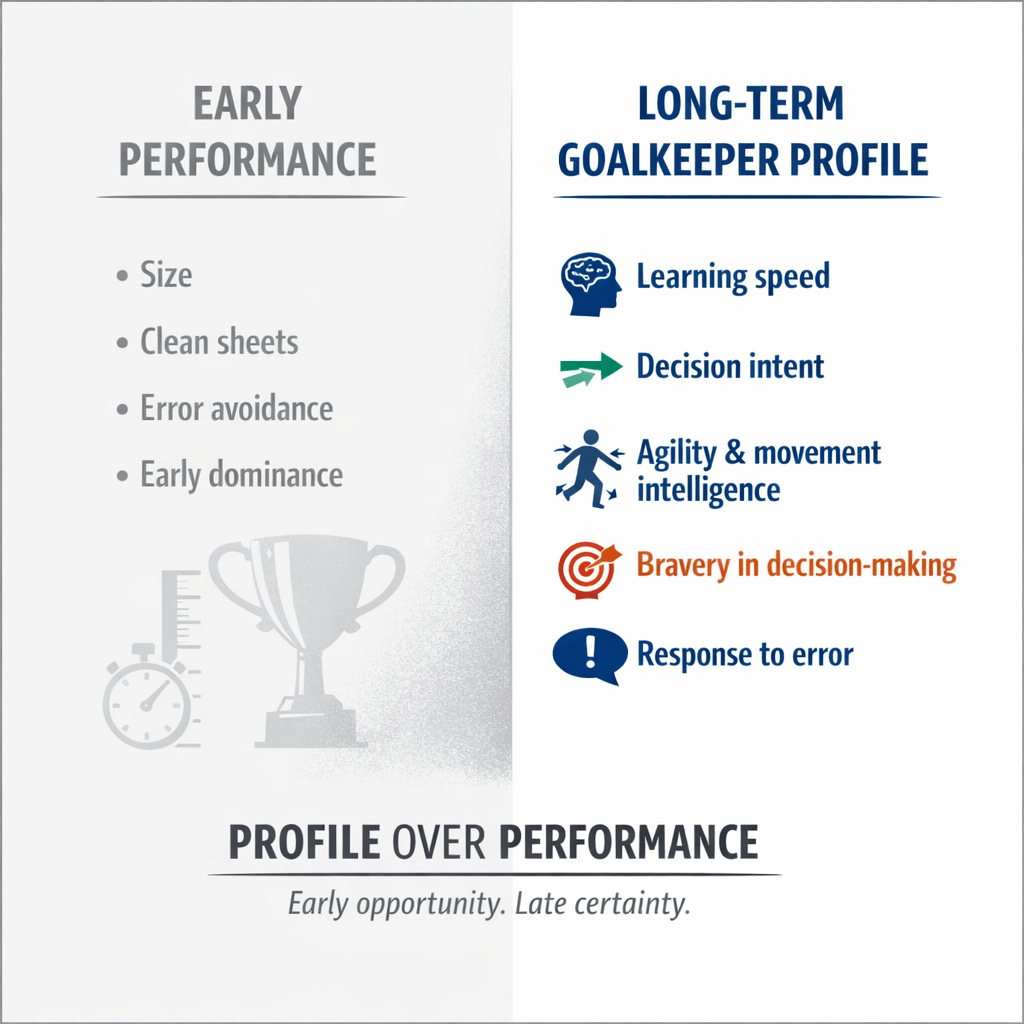

Profile matters more than performance — if defined properly

Most academies recruit to a “profile”. That’s sensible.

The issue is that, at very young ages, profiles can quietly become performance proxies, rewarding:

- Size

- Error avoidance

- Early dominance

- Physical presence

Elite goalkeeper pathways suggest something different.

At the youngest ages, the most useful profiles are future-facing, not outcome-based.

They prioritise:

Learning and thinking

- Learning speed

- Curiosity and engagement

- Decision intent (even when decisions are wrong)

Psychology

- Response to mistakes

- Emotional regulation

- Bravery expressed through decision-making, not recklessness

Movement intelligence

- Agility in all planes

- Twisting, turning, and recovering

- Balance and body awareness

- Control under instability

This isn’t about power, reach, or explosiveness.

It’s about how a child moves, not how big or fast they are.

Game bravery (correctly framed)

- Willingness to narrow angles

- Engagement in 1v1s

- Commitment once a decision is made

Not repeated collisions. Not fearlessness.

Elite goalkeepers scale decision courage, not physical bravado.

The cost of early certainty

When early goalkeeper decisions are treated as predictive rather than provisional:

- Late developers are released too early

- Retention windows shorten

- Acquisition becomes the default fix

- Long-term costs increase financially and developmentally

Early certainty feels efficient.

Over time, it often isn’t.

A better way forward

If early goalkeeper recruitment is operationally inevitable, then uncertainty must be intentionally preserved.

That means:

- Treating U9 recruitment as access, not prediction

- Separating profile from performance

- Retaining a range of developmental profiles

- Measuring success over time, not season by season

None of this requires a new system.

It requires clearer thinking.

For parents, one important message

Early selection by a big academy is not a guarantee.

Early non-selection is not a verdict.

Elite goalkeeper pathways are defined by:

- Early opportunity

- Broad development

- Patience

- Non-linear progress

Understanding that reduces fear and fear is often what drives the worst early decisions.

Final thought

Academies don’t struggle because they recruit goalkeepers early.

They struggle only when early performance is mistaken for long-term potential.

The real competitive advantage isn’t finding the best goalkeeper at nine.

It’s designing systems that allow potential to survive long enough to be recognised.

Profile over performance.

Early opportunity.