Every August-born child in football is already fighting a battle they don’t even know exists.

At six or seven years old, they step onto the same pitch as children who could be almost a full year older—11 months that, at that age, represents about 15% of their entire life. Those months mean differences in height, strength, coordination, cognitive processing and emotional self‑regulation.

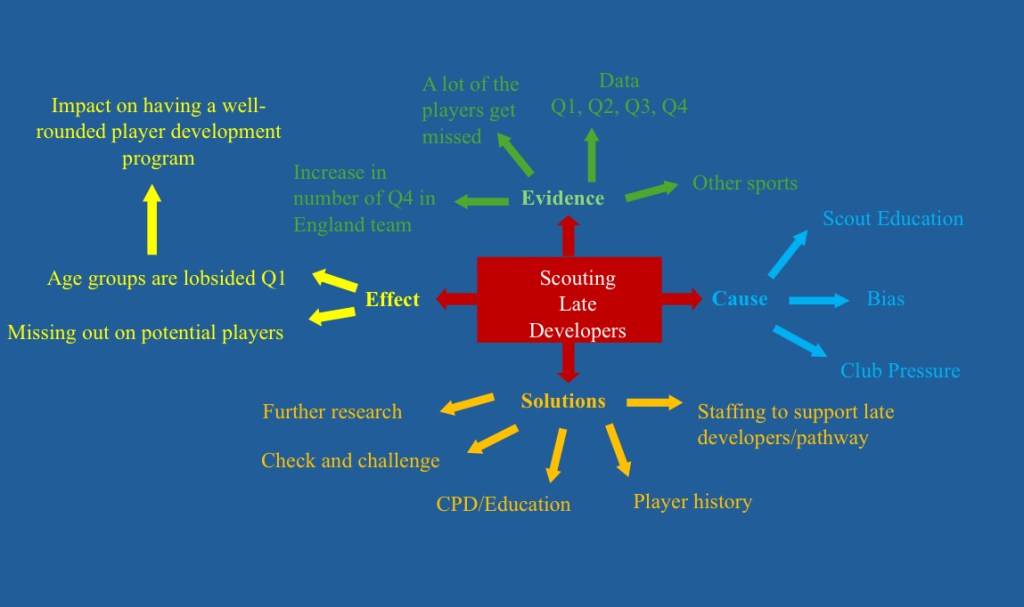

And yet, all too often, coaches (often unconsciously) mistake these maturity differences for “talent.” Early-born children get more touches, more minutes and all too often more praise. Late-born children get fewer opportunities, less confidence, and many simply drift out of the game. This is the Relative Age Effect in action.

The Data Speaks Volumes

When we look at England’s academy system, the bias is clear:

- Q1 (Sep–Nov): 44%

- Q4 (Jun–Aug): 11%

Nearly half of all academy players are born between September and November. Those born between June and August? Just one in ten.

Now compare that with the senior squads at Euro 2024 by birth quartile:

- All 571 senior players:

- Q1: 23%

- Q4: 21%

- England Senior Men’s Squad:

- Q1: 27%

- Q4: 27%

The contrast is striking. By the time players reach the elite level, the distribution of birth dates is almost even. So why are we losing so many Q4 players so early on and favoring those players born in Q1? Because we are dismissing them long before they’ve had the time or opportunity to catch up.

Performance vs. Potential

At U6–U8, talent identification is tricky. We are not just selecting players—all too often we are inadvertently selecting maturity. That’s a dangerous game. An August-born player might look “behind” today, but with the right support and time, they could well overtake their peers in adolescence.

Focusing on long-term potential over performancerequires:

- Extending observation windows.

- Benchmarking by relative age and maturity, not just chronological age.

- Offering flexible entry and re-entry points into development centres

- Training coaches to check their biases and look beyond immediate obvious physical advantages.

- Communicating with parents, so expectations are realistic and patience is encouraged.

Why This Matters

This is not just a moral issue—it’s a performance issue. By overlooking late-born players, we’re not only being unfair, we’re weakening the talent pipeline. Players born later in the selection year who leave the game too early because they weren’t deemed “good enough” at six or seven despite having certain key outstanding characteristic(s) could potentially be a future star.

I’ve seen first-hand the difference when pre-academy environments embrace this challenge. The talent pool widens. Confidence grows. And the overall standard of players in the longer term improves because the system is built to support children irrespective of when they were born, not just the early developers.

A Call to Action

The Relative Age Effect has been known for years, but awareness alone won’t fix it. We need collective action—systematic changes in how we identify, develop, and retain the very youngest players with late birthdays.

It’s time we stop penalising children for the month they were born. If we truly want to find the best players and create the best version of our game, we need to challenge our own assumptions and build a pathway that’s fair.